Janet R. Kirchheimer

From How to Spot One of Us

From How to Spot One of Us

Take a number please,

the dispenser reads

at the butcher’s.

I take one and wait in line.

It’s before Shabbos, everyone is rushed,

people pushing or being pushed,

trying to get to the counter, to get their food,

someone mutters, “I was ahead of you.”

“Who’s next?” says the butcher,

and panic falls from me like a puzzle

dropped on the floor and I can’t

find all the pieces and the ones I can

pick up don’t fit together anymore and

I want to tell them about my father’s

sister and how her visa number was too

high and there were too many people in

line ahead of her waiting to get out and how

she was deported to

Auschwitz and she didn’t get

a number there and if she had, she

might have survived and

I want to tell them about my friend’s mother, how

she got a number on her forearm in

Auschwitz, and how she got a

visa number after the war and about the

dreams she has every night and

the butcher calls my number, and I

cannot make a sound.

I remember my father driving to the hospital, my mother

yelling at him to slow down, afraid the police

would stop them, the nurses telling him to go home,

it would be a long time, and the nurses wheeling her

into the delivery room, her screams, the drugs,

my father back after only two hours,

and I remember the red roses he brought her,

her asking how much they cost, they had no money, and

my mother’s face, her green eyes, her blond hair as she held me,

her olive-skinned girl with a mess of black hair, wondering

if they gave her the wrong baby, and hearing my name,

“Janet,” after Oma Kirchheimer, and “Ruth,” after my father’s sister,

and the woman in the next bed telling my mother

the nurses asked if a Jew could share her room.

My father is teaching me German.

He still speaks fluently, even though he

escaped from Nazi Germany almost

seventy years ago when he was seventeen.

We study nouns and verbs.

We study when to use the formal pronoun, Sie, you

and when to use the more familiar, Du.

One must be offered permission to use the familiar.

We study dialects.

The word Ich, I.

The Berliners pronounce it Ick.

Those from Frankfurt am Main, Isch.

Those from Schwaben, Ich or I.

He tells me when he was a kid he and

his friends used to say in a Berliner dialect,

“Berlin jeweesen Oranje jejessen und sie war so süss jeweesen.”

I was in Berlin and ate an orange, and it was very sweet.

“And then we added, dass mir die brüh die gosh runterglaufe is,”

with the juices running down my mouth.

He explains: “It is in our Schwäbisch dialect.

I should say, it was our dialect.”

My mother’s cousin Ilse went to school

with Margot Frank, Anne’s older sister.

Sometimes I dream that they met at Ilse’s home

on the Schubertstraat and Margot brought her little sister along.

Ilse’s mother served them tea and cookies,

and Hanni, Ilse’s little sister, played with Anne

and the older girls talked about the boys they liked,

the teachers they didn’t, what they would do

during summer vacation, what they would be when they

grew up. Ilse wanted to be a doctor.

Sometimes I dream they were all together

in the same barracks in Bergen Belsen, that Ilse begged

Margot and Anne to live after they contracted typhus, and

that Ilse told them they would get better and

they would meet for tea at a nice café in Amsterdam after the war.

Ilse returned, along with her mother and sister.

They lived in a small apartment, and Hanni, the one who

had been experimented on, rarely came out of her room.

Their father did not survive.

Ilse went back to school and became a doctor.

Sometimes I dream I’m the one who kills Hitler.

It’s simple. I walk up to him,

shoot him in the face, and watch his head

explode into a million

glass pieces that clink on the floor

like a Saturday morning cartoon character’s.

Except he doesn’t get back up.

And sometimes I am Yael.

I invite Hitler into my tent as he flees from his enemies.

He tells me he is thirsty, and I

give him milk, and he falls fast asleep.

I pick up a tent pin and hammer. I drive the pin

through his temple until it reaches the ground.

Other times I’m part of the plot to assassinate him

aboard his plane. This time I make sure

the bomb explodes. He falls faster and faster, crashing

with such force the earth swallows him up, as if he never

existed, and I’m sitting on the back porch, the sun is shining,

and all my grandparents, cousins, aunts, and uncles

are laughing and telling stories.

My mother, four years old, blond curls,

wearing a smocked dress, in a field of goldenrod,

her doll on her lap and her dog at her side.

Two years later, the girl in the photograph

would be backed up against a wall at school,

by kids in her class for refusing to say “Heil Hitler,”

and they would throw rocks, beat her up, call her Jude,

her dress would be torn, and her parents

would have to find a way to get her out of Germany.

She would be sent to an orphanage in Amsterdam,

and they would wait two years for their visas

to America. I want to ask the girl what

would have become of her if her parents hadn’t

found a way out? Would she have survived?

Would she have been experimented on like her cousin Hanni

Who returned home after the war and rarely

left her room, or would she,

like another cousin, Bertl, have tried to cross the Pyrenees

into Spain and never be heard from again? What if Hitler had never come

to power, would she and her parents still have come to America?

Would she have met my father, and who would

she have married if she had stayed in Germany, and

who would she have become and what would have become

of me? I cannot let go of it.

My mother tells me of the train

ride to the American Consulate in Stuttgart

when she was eight years old,

and of the jewelry that her mother owned,

and the window her mother opened at every bridge,

of the rings, bracelets, and necklaces she threw out

when Jews were ordered to turn in their gold

and silver, saving only her wedding ring.

My mother tells me of the doctor who makes her undress

and makes her mother leave the room.

He listens to her heart, checks for marks and bruises, and

she tells me of the shiny metal object he uses as he spreads her legs.

The visa was stamped, a red ribbon attached to its corner.

And my mother tells me of the red Mary Jane shoes her mother

buys her on the way back to the train and of her excitement

at seeing the statue of the Lorelei for the first time.

She tells me of the legend every German schoolchild learns,

and I sit in the kitchen, listening as my seventy-year-old mother sings me

her song: “I do not know what it should mean that I am so sad,

a legend from old days past that will not go out from my mind.”

the dispenser reads

at the butcher’s.

I take one and wait in line.

It’s before Shabbos, everyone is rushed,

people pushing or being pushed,

trying to get to the counter, to get their food,

someone mutters, “I was ahead of you.”

“Who’s next?” says the butcher,

and panic falls from me like a puzzle

dropped on the floor and I can’t

find all the pieces and the ones I can

pick up don’t fit together anymore and

I want to tell them about my father’s

sister and how her visa number was too

high and there were too many people in

line ahead of her waiting to get out and how

she was deported to

Auschwitz and she didn’t get

a number there and if she had, she

might have survived and

I want to tell them about my friend’s mother, how

she got a number on her forearm in

Auschwitz, and how she got a

visa number after the war and about the

dreams she has every night and

the butcher calls my number, and I

cannot make a sound.

Imprints

From

the womb a fetus looks and can see from the beginning of the world to

its end, and when she emerges, God hits her under the nose and she

forgets everything she saw.

—Adapted from Seder Y’tzirat Hav’lad.

I remember my father driving to the hospital, my mother

yelling at him to slow down, afraid the police

would stop them, the nurses telling him to go home,

it would be a long time, and the nurses wheeling her

into the delivery room, her screams, the drugs,

my father back after only two hours,

and I remember the red roses he brought her,

her asking how much they cost, they had no money, and

my mother’s face, her green eyes, her blond hair as she held me,

her olive-skinned girl with a mess of black hair, wondering

if they gave her the wrong baby, and hearing my name,

“Janet,” after Oma Kirchheimer, and “Ruth,” after my father’s sister,

and the woman in the next bed telling my mother

the nurses asked if a Jew could share her room.

Learning a New Language

My father is teaching me German.

He still speaks fluently, even though he

escaped from Nazi Germany almost

seventy years ago when he was seventeen.

We study nouns and verbs.

We study when to use the formal pronoun, Sie, you

and when to use the more familiar, Du.

One must be offered permission to use the familiar.

We study dialects.

The word Ich, I.

The Berliners pronounce it Ick.

Those from Frankfurt am Main, Isch.

Those from Schwaben, Ich or I.

He tells me when he was a kid he and

his friends used to say in a Berliner dialect,

“Berlin jeweesen Oranje jejessen und sie war so süss jeweesen.”

I was in Berlin and ate an orange, and it was very sweet.

“And then we added, dass mir die brüh die gosh runterglaufe is,”

with the juices running down my mouth.

He explains: “It is in our Schwäbisch dialect.

I should say, it was our dialect.”

Sisters

My mother’s cousin Ilse went to school

with Margot Frank, Anne’s older sister.

Sometimes I dream that they met at Ilse’s home

on the Schubertstraat and Margot brought her little sister along.

Ilse’s mother served them tea and cookies,

and Hanni, Ilse’s little sister, played with Anne

and the older girls talked about the boys they liked,

the teachers they didn’t, what they would do

during summer vacation, what they would be when they

grew up. Ilse wanted to be a doctor.

Sometimes I dream they were all together

in the same barracks in Bergen Belsen, that Ilse begged

Margot and Anne to live after they contracted typhus, and

that Ilse told them they would get better and

they would meet for tea at a nice café in Amsterdam after the war.

Ilse returned, along with her mother and sister.

They lived in a small apartment, and Hanni, the one who

had been experimented on, rarely came out of her room.

Their father did not survive.

Ilse went back to school and became a doctor.

Sweet Dreams

Sometimes I dream I’m the one who kills Hitler.

It’s simple. I walk up to him,

shoot him in the face, and watch his head

explode into a million

glass pieces that clink on the floor

like a Saturday morning cartoon character’s.

Except he doesn’t get back up.

And sometimes I am Yael.

I invite Hitler into my tent as he flees from his enemies.

He tells me he is thirsty, and I

give him milk, and he falls fast asleep.

I pick up a tent pin and hammer. I drive the pin

through his temple until it reaches the ground.

Other times I’m part of the plot to assassinate him

aboard his plane. This time I make sure

the bomb explodes. He falls faster and faster, crashing

with such force the earth swallows him up, as if he never

existed, and I’m sitting on the back porch, the sun is shining,

and all my grandparents, cousins, aunts, and uncles

are laughing and telling stories.

The Photograph in My Hand

My mother, four years old, blond curls,

wearing a smocked dress, in a field of goldenrod,

her doll on her lap and her dog at her side.

Two years later, the girl in the photograph

would be backed up against a wall at school,

by kids in her class for refusing to say “Heil Hitler,”

and they would throw rocks, beat her up, call her Jude,

her dress would be torn, and her parents

would have to find a way to get her out of Germany.

She would be sent to an orphanage in Amsterdam,

and they would wait two years for their visas

to America. I want to ask the girl what

would have become of her if her parents hadn’t

found a way out? Would she have survived?

Would she have been experimented on like her cousin Hanni

Who returned home after the war and rarely

left her room, or would she,

like another cousin, Bertl, have tried to cross the Pyrenees

into Spain and never be heard from again? What if Hitler had never come

to power, would she and her parents still have come to America?

Would she have met my father, and who would

she have married if she had stayed in Germany, and

who would she have become and what would have become

of me? I cannot let go of it.

The Way to a Visa

My mother tells me of the train

ride to the American Consulate in Stuttgart

when she was eight years old,

and of the jewelry that her mother owned,

and the window her mother opened at every bridge,

of the rings, bracelets, and necklaces she threw out

when Jews were ordered to turn in their gold

and silver, saving only her wedding ring.

My mother tells me of the doctor who makes her undress

and makes her mother leave the room.

He listens to her heart, checks for marks and bruises, and

she tells me of the shiny metal object he uses as he spreads her legs.

The visa was stamped, a red ribbon attached to its corner.

And my mother tells me of the red Mary Jane shoes her mother

buys her on the way back to the train and of her excitement

at seeing the statue of the Lorelei for the first time.

She tells me of the legend every German schoolchild learns,

and I sit in the kitchen, listening as my seventy-year-old mother sings me

her song: “I do not know what it should mean that I am so sad,

a legend from old days past that will not go out from my mind.”

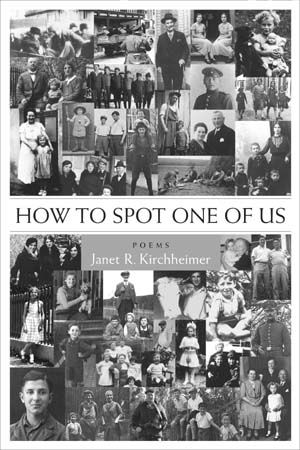

Janet R. Kirchheimer’s moving collection of poems about the Holocaust, How To Spot One Of Us (2007), received endorsements from Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel, Sir Martin Gilbert, and Rabbis Harold Kushner and Irving “Yitz” Greenberg (Chairman Emeritus of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council), as well as poets Mary Stewart Hammond, Yerra Sugarman, and Jeanne Marie Beaumont. Several poems from the book have been translated into Russian and appear on Russian literary websites.

Janet’s work has appeared in journals including Atlanta Review, Potomac Review, Limestone, Connecticut Review, Lilith, Common Ground Review, and on beliefnet.com and babelfruit.com, among others. She was awarded Honorable Mention in the Tiferet 2010 Poetry Contest, was a finalist in the Rachel Wetzsteon Prize from the 92nd Street Y, and received a Citation for her work from The Council of The City of New York. She was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2007. In 2006, she was a semi- finalist in the “Discovery”/The Nation contest and received a Drisha Institute for Jewish Education Arts Fellowship in 2006-2007. Her essay “Make Your Selection, Please” was a Jewish Telegraphic Agency feature article for Yom HaShoah (2006), and her essay, “Kristallnacht: How Will We Remember?” was a special feature in The New York Jewish Week in 2009. A popular speaker, she has appeared on radio programs around the country.

Janet has given several readings and taught at a variety of locales including the ADL/Hidden Child Foundation, Yeshiva University, Fairleigh Dickinson University, YMCA Men’s Club, Brooklyn and Queens Public Libraries, the Association of Jewish Family & Children’s Agencies, the JCC in Manhattan and Washington D.C., Hadassah, Poet’s House, Teachers and Writers, the Bowery Poetry Club, and various synagogues. As part of a 2009 Multi-National Forces Days of Remembrance Holocaust Memorial Service, she helped design the service, video-taped a reading shown at Camp Victory in Baghdad, Iraq, and judged a poetry contest for soldiers. In 2009, she spoke to over 200 high school students at the Westover School for their annual Holocaust memorial service, and in 2010 spoke to 300 fifth and sixth graders from the Yonkers public school system as part of Holocaust Remembrance Week.

Janet is a member of Chevrah Kadishah (the ritual preparation for Jewish burial), as are her parents. Through this experience, as with her poems, she has been able to transform her family’s pain into a moving tribute. “So many members of my family never had a burial and, as the daughter of survivors, the opportunity to give someone a proper Jewish burial is a great honor for me.”

A Teaching Fellow at Clal – The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, Janet conducts leadership development seminars, text study classes, and workshops in which adults and teens explore their Judaism through creative writing and poetry.

These poems are published here with permission of the author.

CLAL, the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, 2007

ISBN 13: 978-0-9633329-8-1, 114 pages

To order, visit the CLAL site or purchase it at Barnes and Noble